Suspected Causes of FCGS

To date, no single cause for FCGS has been identified. The disease is currently believed to be a multifactorial process with infectious agents, host immune response, genetic predisposition, and concurrent periodontal disease each playing a role. In particular, FCGS is thought to be triggered by an exuberant host immune response to the chronic oral antigenic stimulation caused by dental plaque bacteria. This excessive response results in severe inflammation of the oral cavity.

While several infectious agents have been associated with FCGS, no specific agent has been identified as the inciting cause. Bacterial species Pasteurella and Prevotella appear to be more highly represented than other species in the dental plaque of cats with FCGS. Feline Calicivirus has also been implicated, with some studies showing up to 97% of cats with chronic oral inflammation carrying the virus. Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) have also been implicated as possibly predisposing cats to the development of FCGS. However, it is important to note that a true cause and effect relationship has not been established for any of these infectious agents.

Clinical Signs

Cats are stoic creatures, and many cats with periodontal disease will continue to eat and drink normally despite oral pain. Cats with FCGS are often severely painful and may exhibit signs such as:

- Partial to complete loss of appetite

- Preference for canned food and reluctance to eat hard food

- Weight loss

- Excessive salivation, blood-tinged saliva

- Pawing or rubbing the face

- Dropping food

- Halitosis

- Abnormal swallowing

- Pain when chewing, yawning, or opening the mouth

- Swollen, ulcerated, or bleeding gums

- Unkempt appearance due to a decrease in self-grooming

- Hiding, reclusive behavior

Diagnosis of FCGS

As with any dental condition, the diagnostic process first begins with a thorough history and an examination of the oral cavity. History should include discussion of the patient’s diet, concurrent medical conditions, clinical signs, and age at onset of the disease. The oral examination is best accomplished under general anesthesia and should include full mouth radiographs to evaluate disease beneath the surface. Practitioners should note that while routine gingivitis is typically confined to the gingival tissues, lesions in FCGS extend beyond the mucogingival line.

Blood work, urinalysis, and thyroid panel are also recommended for all cats with suspected FCGS to rule out underlying disease. Additional testing such as FIV/FeLV test, calicivirus PCR, and Bartonella screening may be useful in some cases.

Differential diagnoses for FCGS include other causes for extensive oral inflammation such as eosinophilic granuloma complex, food allergy, neoplasia, uremic stomatitis, and ingestion of caustic or irritating substances. These differentials should be ruled out prior to proceeding with treatment for FCGS.

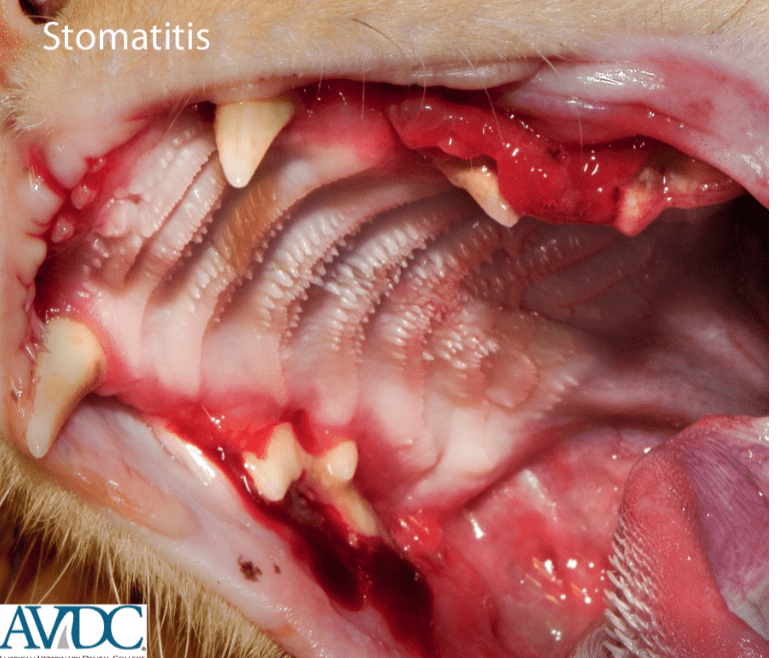

Typical clinical appearance of a cat suffering from FCGS

Treatment

Due to the multifactorial etiology of FCGS, there is no single treatment that is effective in all cases. Unfortunately, treatment is often frustrating and can be unrewarding. Good client communication regarding costs, prognosis, and home care is essential in order to promote client compliance.

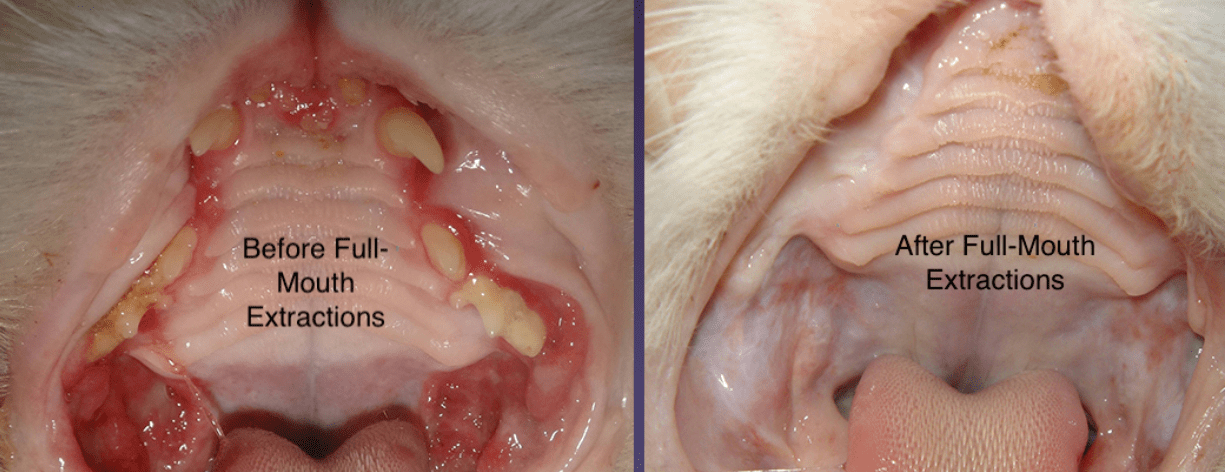

The gold standard treatment for FCGS is partial or full mouth extraction. This significantly decreases the oral antigen burden and removes the nidus for inflammation. In some cases, removal of the molars and pre-molars is sufficient. In others, full mouth extraction is necessary in order to adequately control inflammation. If extraction is to be performed, it is critical that all structures are completely removed and no tooth root remnants are left behind. Post- operative full mouth radiographs are also required in order to ensure all roots have been removed. Referral to a veterinary dentist is often recommended for this procedure.

If extraction is not possible, medical therapy may be used as a primary treatment, though this is often unrewarding. More commonly, medical therapy is used as an adjunctive treatment in cases where extraction alone does not achieve a clinical cure. Medical therapy is typically multimodal and the goal is to reduce pain, eliminate infection, and modulate the host’s immune response. Medical treatment for FCGS may include:

- Antibiotics to reduce oral bacterial load

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as corticosteroids

- Immune-modulating drugs such as cyclosporine or interferon

- Laser therapy

Supportive therapy such as vitamin and fatty acid supplementation, fluids, and critical care diets It is particularly important to note that antibiotic therapy should never be the sole method of treatment in cases of FCGS. While antibiotics can decrease bacterial load and provide some short term relief, they ultimately provide little benefit and predispose the cat to development of resistant infections. In cases where full mouth extraction is to be performed, most veterinary dentists feel that antibiotic therapy is unnecessary.

Outcomes

A study of the outcomes of 30 cats following full mouth extractions (Hennet, 1997) found that 60% of cats were cured and required no further treatment. Another 20% of the cats studied showed significant improvement, 13% showed only minor improvement, and 7% showed little to no improvement. Similarly, a more recent study (Girard, 2005) demonstrated that full mouth extraction resulted in a cure for 50% of the cats studied, while 37% improved but required adjuvant medical treatment, and the remaining 13% did not improve. Thus, while full mouth extraction provides the best chance at a clinical cure, it is important to prepare pet owners for the possibility that their individual cat may require further medical therapy following extraction.

Perhaps the most common question from pet owners is whether or not their cat will be able to eat solid food following the procedure. While it is best to transition to a canned food diet prior to surgery (and some cats may have already made this choice for themselves due to chronic oral pain), many cats are able to return to eating dry food and treats 2-3 weeks after the procedure. However, in refractory cases a soft diet may continue to be a lifelong necessity.

Summary

Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis is a complex disease, the cause and treatment of which is still poorly understood. Currently, full mouth extractions are recommended as the primary therapy, but medical management may be necessary in refractory cases. In all cases, long term follow up is recommended to monitor for recurrence of oral inflammation.